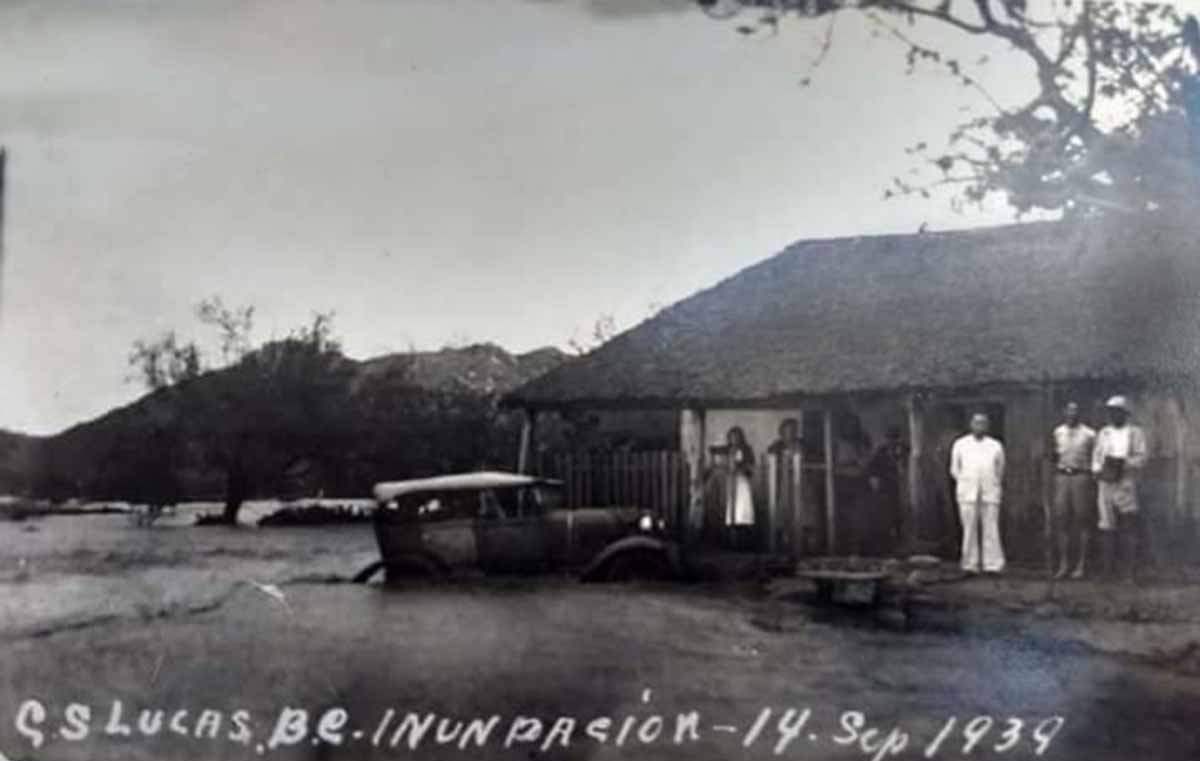

Remembering “La Inundación de 1939”

When the Capes Region first began to be developed as a tourist destination in the 1950s and 60s, warm year-long temperatures were a big part of the attraction. Brochures touted, accurately, the approximately 300 days of cloudless sunshine the region enjoys annually, many during the long cold winters when snowstorms afflict much of the U.S. and Canada. But Los Cabos and the Baja California peninsula also have their storms. They are not frequent but can be devastating in their intensity.

The force and seasonal variation of these storms is reflected in the many terms peninsular residents use for them, words like tormenta, equipata, aguacero, chubasco and huracán. The most violent of these is the chubasco, a late summer or autumn hurricane that typically forms off the Pacific Coast of Central America or southern México, and then churns northward over warm ocean waters with little to no surface resistance. “Their paths,” writer Norman Roberts once noted, “are erratic, often appearing to change course at a whim. When they remain at sea, they do little damage. Those that do reach sufficient size, and move north or northeast from their spawning grounds, wreak havoc when they reach land.”

1939 was a nightmarish year for chubascos in Baja California. Bahía Magdalena, some 170 miles up the Pacific Coast from Cabo San Lucas, was deluged by four chubascos during the month of September, recording a level of precipitation from them that equaled the rainfall the region received during the next 24 years combined! The most ferocious of these cyclonic storms, however, was the one that nearly blew Cabo San Lucas itself right off the map. This was the storm now remembered as la inundación de 1939, when high winds and uncontrolled flooding surged over the territory’s southernmost communities in a raging torrent.

“1907, 1918, oh much suffering; another one in 1927, many animals and fruit trees lost,” recalled local historian and professor Fernando Cota in C.M. Mayo’s superb 2002 travelogue Miraculous Air. “And then there was the chubasco of 1939…Some people rode it on horseback from Cabo San Lucas – it was impossible to cross El Tule in an automobile – and they told me when they passed by the school: Cabo San Lucas is gone! So we went there on horses. We sent some mules across El Tule first because they are more surefooted, and if they can cross, the horses follow. We rode and walked through the night and we arrived at sun-up. From the sea to the foothills of the sierra there was nothing but broken pieces of cardón cactus. There were no references, everything had disappeared.

“Not many died, only five, because the chubasco came down in the daytime. Had it been at night, that would have been different. But they lost everything, their clothes, their dishes, their beds. Forty families! The Governor, Lt. Col. Rafael M. Pedrajo, he delivered the material for 40 houses! I don’t know how he did it. The floors and walls were of wood, the roofs of corrugated iron. For 40 families! Incredible, such a work. They should put his name on a street, a monument, something.”

Lt. Col. Pedrajo has yet to be honored for his improvisational heroics and strong leadership in the face of enormous adversity, at least in Cabo San Lucas; there is a street in the pueblo mágico of Todos Santos that bears his name, one that dead-ends at a scenically situated restaurant called El Mirador. Perhaps the emotional aftershocks of the hurricane and its crippling effects were so profound that residents preferred not to remember it with public monuments, lest the memories come flooding back as furiously as the waters that had overrun their roads and the screaming winds that had ripped the roofs from their homes and snapped mature trees like matchsticks.

Certainly, the storm haunted Sanluqueños for a long time afterwards, its lingering pall noted by famed author and future Nobel Prize winning novelist John Steinbeck when he visited the town the following year. Steinbeck and his marine biologist friend Ed Ricketts–memorialized as the character “Doc” in Cannery Row–had embarked on a voyage to the Sea of Cortés aboard the Western Flyer in order to collect marine invertebrate specimens, a journey remembered in the book Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research (later abridged and republished, somewhat more successfully, as The Log from the Sea of Cortez).

“We went ashore to the cannery and later drove with Chris, the manager, and Señor Luis, the port captain, to the little town of San Lucas,” Steinbeck wrote. “It was a sad little town, for a winter storm and a great surf had wrecked it in a single night. Water had driven past the houses, and the streets of the village had been a raging river. ‘Then there were no roofs over the heads of the people,’ Señor Luis said excitedly. ‘Then the babies cried and there was no food. Then the people suffered.

“The road to the little town, two wheel-ruts in the dust, tossed us about in the cannery truck. The cactus and thorny shrubs ripped at the car as we went by. At last we stopped in front of a mournful cantina where morose young men hung about waiting for something to happen. They had waited a long time – several generations – for something to happen, these good-looking young men. In their eyes there was a hopelessness. The storm of the winter had been discussed so often that it was sucked dry.”

In a cruel twist of fate, Hurricane Odile, the category-4 hurricane that devastated Los Cabos in 2014, happened on the very same day as la inundación de 1939: September 14. During the intervening 75 years, however, the entire landscape of the region had been transformed, and the populations of cape communities Cabo San Lucas and San José del Cabo multiplied exponentially, driven inexorably upwards by the municipality’s spiraling popularity as an international tourist destination.

All that was still very much in the future, however, when Steinbeck visited in 1940. Not even the region’s pioneer builders and developers had yet grasped its enormous potential. The only man at the time with vision so far-seeing as to almost pierce the future was Francisco J. Múgica, the man who had replaced Pedrajo as governor. As early as 1941, Múgica dreamed of a system of paved roads, a transpeninsular highway that would connect the southern territory to its northern neighbors.

That dream would ultimately be realized, but not until another three decades had passed, and a storm of a different sort was rocking El Sur.

Want your business, activity or event featured and promoted by CaboViVO, please be sure to contact us here, thanks…

Saludos from Co-Founders…

Chris Sands – Writer and Michael Mattos