The Baja California peninsula has, since the very beginnings of its human history, been a maritime culture; and thus subject to maritime disasters.

Barks and canoes of native fishermen were sometimes blown out to sea. Spanish galleons plying the lucrative Manila–Acapulco trade route were attacked by pirates as they attempted to take on fresh water in what is now San José del Cabo. Sailboats perished in the seasonal storms that wracked the Sea of Cortés, steamships ran aground near outlying Pacific islands. Warships were cannonaded, whaling brigs and sea otter hunters foundered, fishing trawlers were broken upon rocky shores. A few ships were even sunk voluntarily to drive dive-related tourism.

These legendary shipwrecks and their ill-fated crews are as much a part of the history of Baja California Sur as the indigenous peoples, missionaries, ranchers and developers who helped tame a rough and rugged land.

San Juanillo – 1578, Secret Location

In 1565, two Spanish navigators, Alonso de Arellano and Andrés de Urdaneta, made a propitious discovery: in order to catch the Kuroshio Current to travel from Manila to Acapulco, boats were obliged to sail north as far as Japan before crossing the Pacific to California. The resulting two and a half century galleon trade filled Spain’s colonial coffers, as each year Mexican silver was sent to Manila to purchase Chinese silks, porcelain and other Asian luxury goods. The first of these galleons to come to grief was the San Juanillo, which ran aground somewhere between Tijuana and Cabo San Lucas in late 1578 or early 1579, spilling her riches onto the sand. The actual location, described only as a desolate and remote stretch of coastline, has long been a closely held secret. Beachcombers discovered pieces of Ming Dynasty porcelain in the 1970s, and other precious treasures were later salvaged by the INAH (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia) in cooperation with San Francisco based nautical historian Edward van der Porten.

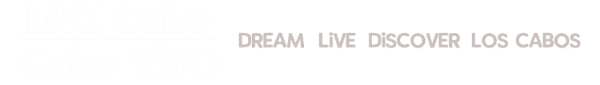

Santa Ana – 1587, Cabo San Lucas

The immensely lucrative Manila–Acapulco Galleon Trade proved irresistible to English and Dutch pirates, who would often use the Land’s End headland in Cabo San Lucas as cover, lying in wait for the treasure laden ships as they rounded the cape to take on fresh water in San José del Cabo. Privateers led by 27-year-old English sea captain named Thomas Cavendish famously sacked the Santa Ana on November 4, 1587, after a six-hour sea battle between the galleon and Cavendish’s smaller, more maneuverable ships, Desire and Content. The English freebooters took a fortune off the Santa Ana before offloading her crew on what is now Médano Beach and setting her ablaze. Amazingly, Spanish crew led by Manila trader and future California explorer Sebastián Vizcaíno were subsequently able to restore Santa Ana to seaworthiness, sailing her to the Mexican mainland. Cavendish and Desire regained England with their riches. Content was lost at sea, giving rise to innumerable rumors of buried treasure along the coastline of present day Baja California Sur.

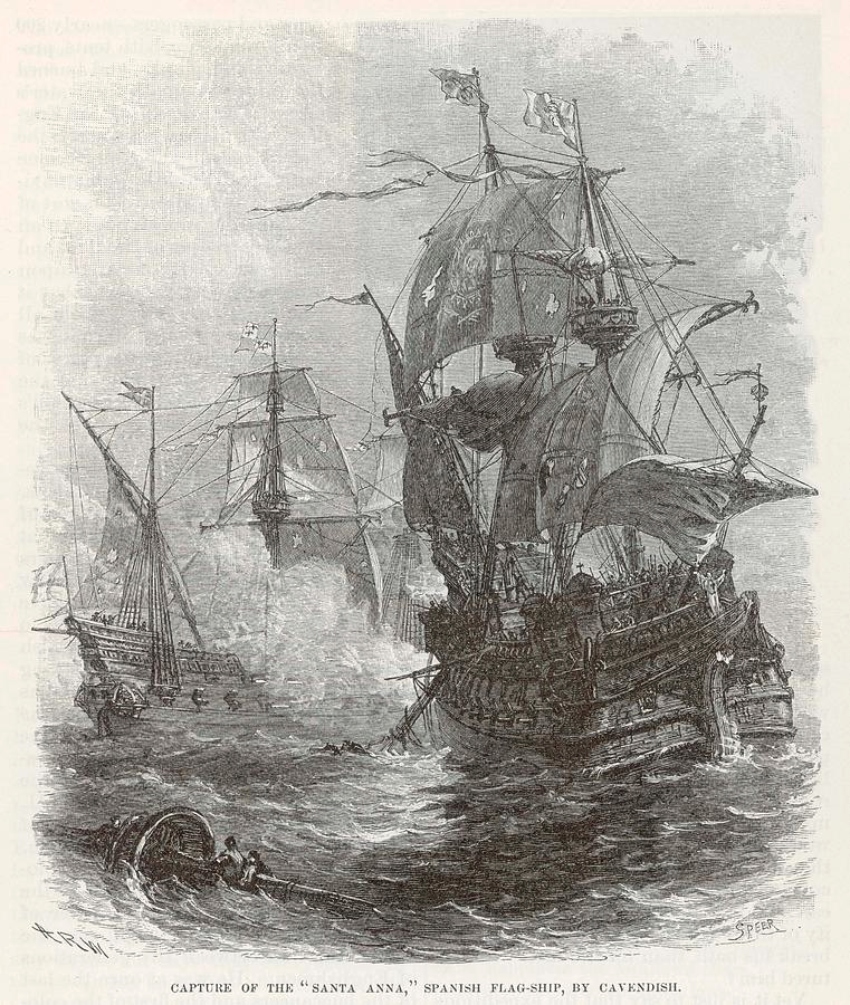

El Triunfo de la Cruz – 1737, Isla San José

Plagued for years by the difficulty of getting supplies from the mainland, Jesuit missionary Juan de Ugarte decided in 1719 to build a ship, the first ever constructed on the Baja California peninsula. Assisted by an English shipwright named William Strafford and Cochimí Indians, Ugarte used native güéribo trees for timber, hauling the wood down from the mountains to Mulegé, where El Triunfo de la Cruz (The Triumph of the Cross) was launched on September 14, 1720. This ship – estimated to have been some 50 feet in length – did dutiful service for well over a decade, making over 70 trips to the mainland. She was lost off the coast of Baja Sur in 1737 after transporting Yaqui reinforcements to Nuestra Señora de los Dolores Apaté, a mission that acted as a military headquarters during the Rebellion of the Pericúes. Fittingly, El Triunfo de la Cruz rests forever beneath the sea she crossed so many times.

Independence – 1853, Isla Santa Margarita

Bound from San Juan del Sur, Nicaragua to San Francisco, the sidewheel steamship Independence was within 300 yards of shore when she struck a rock on February 16, 1853, and immediately began taking on water. When attempts to free her failed, the ship quickly sank near Punta Tosca, at the southern tip of Isla Santa Margarita. An article in the April 2nd edition of the San Francisco newspaper Daily Alta California reported that “Females could be seen clambering down the sides of the ship, clinging with deathlike tenacity to the ropes, rigging and larboard wheel. Some were hanging by their skirts, which unfortunately, in their efforts to jump overboard, were caught, and thus swung, crying piteously and horridly, until the flames relieved them from their awful position by disengaging their clothes, causing them to drop and sink in the briny deep.” Tragically, 132 of the 415 passengers and crew drowned or were burned to death when the boilers caught fire. The survivors justifiably accused Capt. Sampson of gross incompetence. The captain, for his part, maintained that he mistook the rocks for whales. It was one of the worst disasters in the history of Pacific steamship trade, and sadly not the last nautical mishap in the Magdalena Bay region. Another steamer, Golden City, went aground on neighboring Isla Magdalena in 1870.

USS H-1 Submarine – 1920, Isla Santa Margarita

Commissioned in 1913, USS H–1 (also known as SS–28, or the Seawolf) was en route from the Panama Canal to San Pedro when she submerged for the final time on March 12, 1920. To this day, no one really knows whether the submarine was grounded intentionally by being rammed into a shoal near Punta Redonda. Well, no one outside of the U.S. Navy, and they’re still not telling. Edward W. Vernon, in his A Maritime History of Baja California, conjectures that the captain purposely grounded her off Isla Santa Margarita to save his crew from chlorine gas, which was leaking from the batteries. Whatever the cause of her demise, the captain – Lt. Commander James R. Webb – was unable to save himself. He and three of his crew drowned while trying to swim to shore. The U.S. Navy tried but failed to salvage the Seawolf, pulling her off the shoal but losing her in 50 feet of water. The wreck was rediscovered by divers in 1992, and in an ongoing effort to protect her from looters, a new wreck – a WWII era Canadian merchant ship – was discoverd in 2021.

SS Harry Lundeberg – 1954, Cabo San Lucas

On the 8th day of February, in the year 1954, the SS Harry Lundeberg went to a watery grave at Los Frailes, the rocky sentinels that mark the terminus of the half-mile Land’s End headland. Although built in Vancouver in 1943, the cargo ship was under Panamanian registry, and was transporting a load of gypsum plaster from Isla San Marcos, just off the coast of Santa Rosalía. Local legend has it that the Lundeberg’s first mate, despondent over large gambling losses during the voyage, knowingly steered the ship to her doom. The wreckage was buried for many years, but was partially uncovered in 2014, when the Category–4 Hurricane Odile brought her forward half to the surface. After a brief vogue as a dive destination, the wreck was covered again when another storm remapped the seafloor around Land’s End.

Inari Maru – 1965, Playa Barco Varado

The first recorded visit by Japanese to the Capes Region was in 1842, when sailors from a Japanese coastal vessel that had blown out to sea were rescued and put ashore in Cabo San Lucas, then home to approximately 30 to 40 residents. In the early 20th century, the Mexican government sought to increase its revenue streams by granting commercial fishing concessions to select Japanese corporations. Several of these Japanese fishing vessels were ultimately run aground, most notably the Inari Maru, a longliner that foundered on rocks in 1965, six miles northeast of Cabo San Lucas. Waves have since washed the wreckage clean, but the mishap remains entrenched in collective memory thanks to the beach’s subsequent moniker: Playa Barco Varado, or Shipwreck Beach. The place where the crew went ashore is now the grounds of a luxury resort called Grand Fiesta Americana Los Cabos Golf & Spa.

Fang Ming – 1999, Isla Espíritu Santo

On April 18, 1995, the Mexican Navy intercepted a Chinese ship called the Fang Ming, which was illegally transporting 157 immigrants to the U.S. Two years later, another Chinese ship carrying 79 undeclared passengers met a similar fate. The unfortunate immigrants were deported back to their country of origin, but the ships were seized and held at Puerto San Carlos, a fishing port on the coast of Magdalena Bay. There local conservationists hatched a plan to turn them into the first ever intentional artificial reefs off the Baja California peninsula; which, after the two vessels were cleansed of fuel and other pollutants, was accomplished near Baja California Sur’s capital city of La Paz in 1999. The 185’ Fang Ming was sunk in 70 feet of water off the west side of Isla Espíritu Santo, and now hosts thriving colonies of fish, mollusks and sea turtles. The smaller ship, recorded only as NO3, was sunk soon after off Isla Ballena. These are the latest, but surely not the last of Baja Californis Sur’s legendary shipwrecks.

Want your business featured in our directory and promoted by CaboViVO, please be sure to contact us here, thanks…

Saludos from Co-Founders…

Chris Sands – Writer and Michael Mattos